For

my graduation present, my grandma, my aunt, and I went to England. We ranged in

age from 75 to 21, and our social, political, and moral stances varied

similarly. As did our bedtimes.

I

spent much of the time trying not to look like a tourist. This was made

particularly difficult because Grandma is a big fan of maps. Maps of London,

tube maps, bus maps, maps of special sections of town. She carried them with

her and pulled them out every few blocks.

I

did what I could to make her look like a local. At a crucial moment, I talked

her out of a fanny pack.

She

got a single strap backpack instead, which was much less conspicuous.

Eventually

I gave up on disguising us. Instead, I tried to migrate the trip to quaint

places outside of London where being a tourist would have some novelty value.

Grandma was intent on taking me to Stratford-upon-Avon to see Shakespeare.

Aunt

and I both dreaded this part of the trip, because Stratford-upon-Avon

collects tourists like Disney World.

“Look,”

we said, “we made friends in Gloucester! Let’s stay.”

But

it was no use. She was determined that I needed to see Shakespeare. I felt

stereotyped as an English major and suckered into a tourist trap.

Sure

enough, the whole town seemed to have invested in Shakespeare’s name. Every

shop had bobble heads, quotes, stuffed Shakespeare dolls. The streets milled

with Germans, Americans, visiting Englishmen, and Scots. All the buildings,

even the ones erected in the last twenty years, had been designed to resemble the

seventeenth century. It felt like Busch Gardens.

Grandma

took me to Shakespeare’s birthplace and nudged me in. Aunt advised that I

should accept this gift, despite the £16 charge, for the sake of Grandma’s

feelings.

They

made you go through a few rooms with odd relics of Shakespeare’s past and a few

dramatic videos full of quotes—just a trick to control the volume of people visiting the birthplace. I had this particular session to myself, so I sullenly sat in

the handicapped section and watched impassively. I moved through the timed doors one by one as I edged closer to Shakespeare's first home.

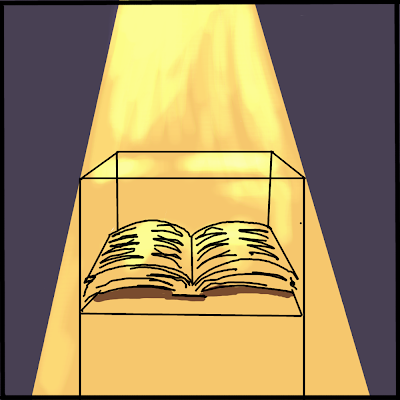

Then,

all of a sudden, the video faded and a light shone on a pedestal in front of

me. “It is thanks to this collection of folios compiled by actors that

Shakespeare’s work has been preserved.”

I

stumbled forward so fast the handicap chair was still folding back up by the time I

reached the pedestal. I got close enough to fog the glass, trying to absorb as much of that page of Richard III as I could in the twenty seconds left on the video.

I tremblingly toured the birthplace, trying to play it cool in front of all the nice interpreters.

I tremblingly toured the birthplace, trying to play it cool in front of all the nice interpreters.

After

my tour, an actress named Charlotte gave me a personal performance of Hamlet's to be or not to be soliloquy. She perched on the edge of a fountain and I think she channeled Shakespeare for a moment there, since I thought not about Hamlet's dilemma, but Shakespeare's own fear of mortality and the beyond.

Shaken and a little stirred (emotionally), I retired for the day, happy with my findings but ready to get back to some less touristy areas.

The next morning, Grandma announced we were going to church. I’d forgotten it was Sunday. Time is relative over there, anyway, since the sun sets at 9:30. Grumblingly, I attended the Holy Trinity Church with Aunt and Grandma.

Afterwards, I retreated to the cemetery with Aunt while Grandma socialized. After ages of waiting for Grandma to finish making friends, she came out with a middle aged woman.

“We have something to show you,” Grandma said. I followed the two back into the church, and the woman walked us past a rope barrier some members of the church were putting up.

And then I saw it. Shakespeare’s grave.

The

woman watched me, waiting for my pleased response and probably a thank you.

Instead, for the first time in years, I cried in public.

For

all my talk, Grandma was right. I wasn’t too cool for Shakespeare.